Following Menton’s annexation into France in the year 1861, an extensive process of urbanisation began. This urbanization was made necessary by the incredible influx of visitors which coincided with Menton’s integration into France. Thanks to a new access to French national resources and the infusion of money into the city economy from visitors, the city was able to begin the construction of new neighborhoods and infrastructure. In order to investigate the forms in which Menton’s urbanization took place, members of this team visited both Menton’s Heritage Exhibit and its city library. At the Heritage Exhibit, miniature replications of Mentonnais architecture helped us to determine which buildings merited further investigation. At the city library, we were directed towards the books Histoire de Menton by Jean Paul Pellegrinetti and Quand Menton recevait l’Europe: des pensions aux palaces, un siècle d’hôttelerie mentonnaise by Jean-Claude Volpi. Both of these books contained information on the urbanization of the city following 1861 and on its most famous buildings and architects. The most relevant of these are discussed below.

Menton’s Famous Architects: Abel Glena and Alfred Marsang

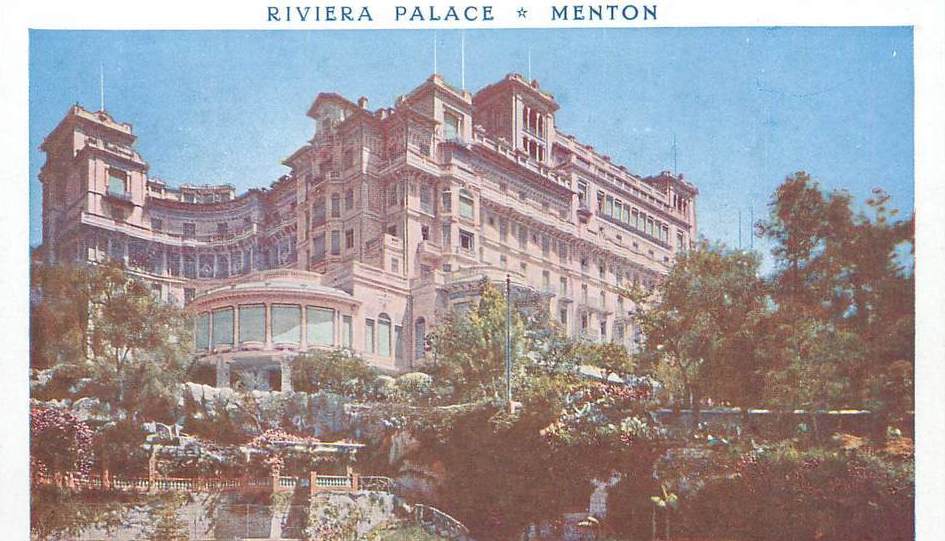

From 1861-1914 in particular, the city of Menton began to undergo significant architectural developments in reaction to the increasing number of visitors the town began to receive. Two architects were notably involved in the process of architectural urbanization in Menton: Abel Glena and Alfred Marsang. Both were born in Menton, Glena in 1862, just one year after Menton’s annexation, and Marsang in 1878. Marsang went on to be educated in architecture in Paris at l’Ecole des Beaux-arts. During his time at university, Marsang studied the architectural style of Henri Deglane, a French architect, and utilized his education to help in the expansion of his home city. Both architects were involved in the creation of new hotels, villas, and the general architectural development of the city in the period directly following Menton’s attachment. For instance, their most well-known project, the Hôtel Riviera-Palace, pictured above, was constructed by Glena and Marsang between the years 1898 and 1901. Labeled as a French heritage site in 2001, this three story building was one of the first “hotel-palaces” the city constructed in order to house influential visitors. Besides Glena and Marsang, another famous Mentonnais painter, Guillaume Cerutti-Maori, also worked on the Hôtel Riviera-Palace. Cerutti-Maori created a mural frieze representing different countries on the outer side of the building to appeal to the city’s new international visitors. Glena was also involved in the construction of a children’s hospital, la Fondation Bariquand Alphand, completed in 1905, which reflected the fact that, while Menton’s mild winters had always been considered an ideal place for those of ailing health, it’s renown as a location of recovery grew after its annexation into France and necessitated the expansion of hospital infrastructure. See the section, ‘Post-Annexation Tourism Boom’, to see more about the health tourists of Menton. Furthermore, Glena also worked on La propriété « Mer et Monts » (early 1900s), the Maison de la rue Loredan-Larchey (1910) and the Immeuble Glena (1912). Marsang, on the other hand, worked on the construction of many villas, such as Villa Renee (1914), as well as on the expansion of hotels, such as l’Hotel de Malte (1913) and l’Hôtel Astoria (early 1900s). L’Hôtel Astoria is particularly reflective of the adoption of French architecture into the city of Menton due to its “Haussmannian style” which imitates that of many buildings in Paris (Menton Heritage Exhibit). Now buried in the Cimetière du Vieux Château, Glena and Marsang are generally regarded as two of the most notable contributors to the architecture of the city of Menton. Their extensive involvement in the city’s period of urbanization reflects the flurry of architectural activity which took place as a consequence of France’s annexation in 1861, as well as the adoption of French architectural styles within the city.

Creation of Mural Friezes

Another notable contributor to the architectural expansion which followed Menton’s annexation to France was the painter Guillaume Cerutti-Maori, mentioned above in relation to the Hôtel Riviera-Palace. Cerutti-Maori was instrumental in the creation of the mural friezes which encircle the tops of many of the most beautiful buildings in Menton. The architectural addition of the friezes to Menton’s architecture was said to have been “l’émanation de la belle époque de la cité du citron”, which took place in the period of 1860 to 1930 (Nice-Matin, 2010). These friezes first began to appear following the booming construction of villas, which were the result of Menton’s establishment as a travel destination in the wake of its annexation. These friezes included several themes, such as “Les fruits et les plantes (citrons, glycines, raisins, oliviers), la chasse et la pêche (animaux et références à la mer) et enfin les allégories grecques voire religieuses (angelots et autres scènes antiques)” (Nice-Matin, 2010). During this period, around 500 friezes and painted murals were created in Menton, with the majority of them being created either directly by Cerutti-Maori or with his consultation. Interestingly, several of Cerutti-Maori’s friezes are only now being rediscovered, “car sur certains murs, repeints dans les années soixante, sous la couche de peinture on retrouve des frises datées de Cerutti Maori” (Tricotti). On the attachment of Menton to France and the consequential rapid creation of friezes, the following was said: “Sans l’explosion économique du siècle dernier et le brassage culturel qui l’a accompagnée, il n’y aurait probablement pas de frises peintes aujourd’hui dans le Pays Mentonnais. Mais leur histoire est également indissociable de celle de la famille Cerutti Maori qui, du début du XIXe siècle jusqu’à une période récente, a régulièrement enrichi la patrimoine des décors peints dans cette région” (Hogu). Active during Menton’s period of intense urbanization, a consequence of its integration into France, it is therefore clear that the painter Cerutti Maori was an indispensable contributor to the richness of the city’s architecture and heritage. In regards to the relevance of the broader creation of mural friezes in Menton from the end of the 19th century to the start of the 20th century, while it was not a phenomenon resulting from a deliberate attempt to incorporate French art into the city, the creation of the mural friezes was only made possible by the influx of people and French capital into Menton following 1861. These friezes are therefore a lasting physical consequence of Menton’s annexation and consequential urbanization.

the architectural consequences of menton’s tourist boom

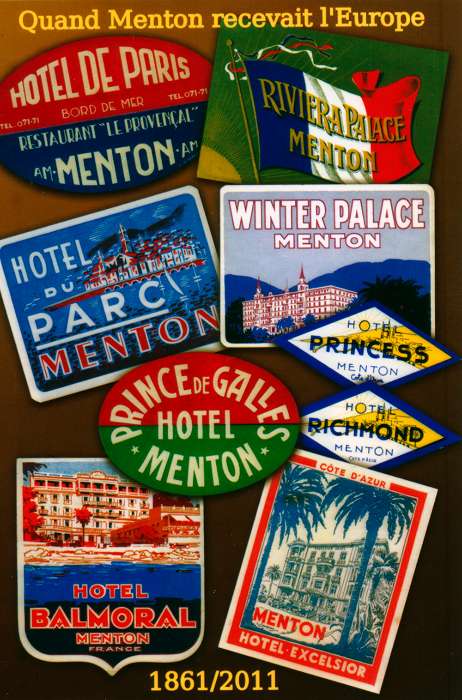

Following Menton’s attachment to France, the city suddenly became accessible to visitors in a way that it had not been under Monaco’s rule. A result of this opening up of the city to the rest of France, as well as to other international visitors, was a tourism boom following the year 1861, which is discussed in ‘Post-Annexation Tourism Boom’. A few short years after annexation, it therefor quickly became apparent that Menton had an insufficient number of hotels to meet the growing demand. In reaction to this demand, one hotel owner, Mr. Dominique Milandri of the Hotel Victoria (now named the Balmoral), organized a petition in 1869 of Mentonnais hotel owners to request that the Promenade de Midi, now the Promenade du Soleil, be extended just up to the point of Cap Martin in order to allow the expansion of the hotel industry in Menton. The municipal county of Menton then voted on 21st of April on this petition and decided to allow construction to begin on the promenade. In addition to this significant expansion, some pre-existing buildings were also converted post-French annexation into hotels, and other hotels were built from scratch. For instance, the Orient Palace was the result of the enlargement in 1874 of a pre-existing building. This iconic Mentonnais building went on to attract international, affluent visitors to the city during the period between 1880-1900. Some of the most notable of these visitors included the Archduke Charles-Louis of Austria, the Baron of Heusch, the Count of Burlet, and the Baroness of Ehrenberg. Another notable hotel in Menton constructed during this time period was l’Hotel de Malte, previously mentioned in its relation to architect Marsang. L’Hotel de Malte was constructed in 1879 and also attracted a cosmopolitan variety of influential visitors, such as the Swiss family Naef Ryhiner (1898), the family of Pierre Leroy-Beaulieu (1898), the Countess of Stainach, the mother of tennisman Georg Von Metaxa (1903), and the Princess Xenia of Montenegro (1905). These two hotels are therefore two architectural marvels only made possible by France’s annexation of Menton in 1861.

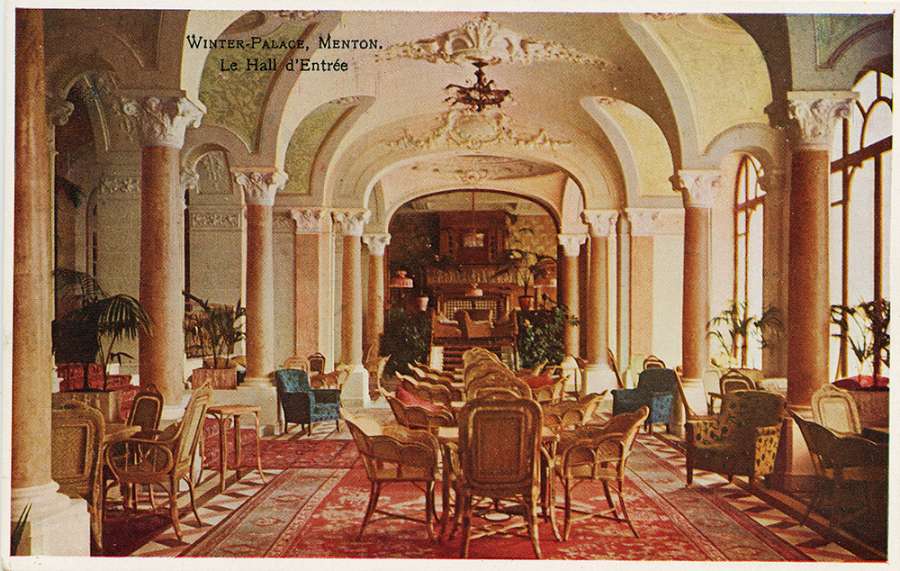

Another architectural wonder of Menton is its Winter Palace. Constructed to appeal to the influx of aristocratic tourists arriving after Menton’s attachment to France, the Winter Palace was constructed during the intense period of urbanization that reshaped the entire city. The hotel’s construction began in 1901, and it opened officially to the public in 1903. The facade of the building was designed in “a combination of the formal style of Louis XVI and Italian charm”, reflecting the Franco-Italian influences pressing upon Menton’s architecture (Winter Palace Website). The Winter Palace originally served as a luxury hotel equipped with “garages, electricity, central heating, lifts, en-suite bathrooms and also a restaurant, smoking room, billiard room, library, card room, and ladies’ salon” (Winter Palace Website). English and Russian visitors, fleeing the harsh winters of their own country, were particularly attracted to the Winter Palace. During the First World War, the Winter Palace was repurposed to function as barracks for soldiers. After a brief period of once again serving the influential visitors of Menton, it was then taken over by both the Italians and the Germans during various periods of Menton’s World War Two occupation. Finally, it even housed the American and Canadian soldiers who liberated the city in 1944. Following WWII’s conclusion, the Winter Palace was converted into private apartments. In light of both its stunning architecture and its unique historical legacy as a residence of France’s elite, its soldiers, its enemies, and its allies, the hotel was added to the French Supplementary Historic Monument List in 1975. It is therefore clear that the building serves as an architectural reminder of the tourist and military consequences of Menton’s attachment to France following the year 1861.

Besides these hotels, one final well known building in Menton, le Palais d’Europe, was also constructed during the urbanization frenzy triggered by Menton’s attachment to France in 1861. The iconic structure began construction in 1908, and was originally the Municipal Casino of the city. Designed specifically to attract influential and international visitors, le Palais de L’Europe contained at its height a multitude of diversions: game rooms, a music hall, an acoustic theater, and ice-skating rink, a restaurant, and one of Europe’s first bowling halls. During the first world war, the large building was converted into a temporary hospital, which altered much of the original interior of the building. It enjoyed a brief period of its former function as a Casino before it was severely damaged during the Italian occupation of Menton from 1940-1943. After it was finally restored in 1965 to account for these damages, le Palais d’Europe became a cultural center for the city. Now, one can attend photo expositions, dance performances, and live music concerts at the Palais d’Europe, making it one of the main artistic hubs of Menton and therefore a lasting physical consequence of Menton’s attachment to France.